Climate: Patterns in the Chaos

This follows Butterflies, Chaos, Feedback. If you’ve not read that already, please read that first – this may not make much sense otherwise!

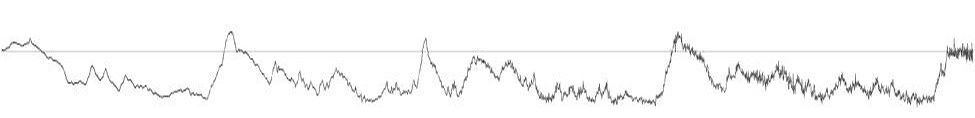

The image shows the changes in global temperature over the last 425,000 years. The range from the minima to the maxima is about ten degrees Celsius. (You may have seen a mirror image of this, with the present on the left, and 425,000 years ago on the right. I like time to go left-to-right, not right-to-left!)

Butterflies, Chaos, Feedback emphasizes the chaotic nature of climate. In much the same way as weather varies unpredictably over periods of a few days yet on average is warmer in summer and colder in winter, so climate varies unpredictably yet within a range. It doesn’t go up or down without limit. This is an example of negative feedback winning in the end.

The range the climate varies over doesn’t have precise limits. The further you get away from the middle of the range, the more unusual it becomes that the climate reaches that particular extreme. In retrospect you can say, "that was the coldest year," or "that was the driest year" – but you couldn’t in advance have categorically stated that no year could possibly be colder or drier.

The range the climate varies over from year to year itself changes from millennium to millennium. There are discernible recurrent patterns in this. When there are recurrent patterns in the behaviour of a chaotic system, it sometimes indicates that there’s a periodic external driving force – but they can also arise internally, within the feedback loops of the chaotic system itself.

Before considering whether the recurrent patterns in climate change are internally generated or due to an external driving force, I’d like to consider where we draw the boundaries of the system anyway. In Butterflies, Chaos, Feedback, I wrote that the ecology and climate of the Earth were both chaotic, and also that each affects the other profoundly. Are they really two separate systems at all, or should we consider them as a single system? That’s an arbitrary choice. As long as you’re aware that each influences the other in a very fundamental way, it doesn’t matter whether you regard the influences of one on the other as external, or regard it all as one more complicated system.

Actually, even the Earth’s geology is also a very closely linked system. At first sight it appears that geology affects climate and ecology strongly, but not much the other way around; but this is an illusion. Plant life removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, reducing the greenhouse effect massively and cooling the planet enough that snow accumulates on land. The weight of ice on bedrock during ice ages, and the associated changes in sea level, are quite sufficient to affect the movement of crustal rocks. Erosion, and subsequent deposition of sediments, is profoundly affected by the climate and by biological action. Nonetheless, the boundary between geology and climate/ecology is rather clearer than that between climate and ecology.

The reduction in weight on Greenland and Antarctica as the ice melts will start the long, slow process of isostatic rebound, the bedrock under the ice – much of it currently below sea level – rising, ultimately by hundreds of metres. Scotland, Scandinavia, and parts of Canada and Siberia are still rising after the removal of the ice from them at the end of the last Ice Age. The rates of rebound in those places is now very slow, a few millimetres a year, but when the ice first melted it was very much faster – and the rebound of Greenland and Antarctica will be relatively fast when the ice first melts, too. (The University of Montana had a good piece on this: Isostasy, now only from the Wayback Machine.) Exactly to what extent the rapid stage of this rebound will cause an increase in the frequency and severity of earthquakes and tsunamis around the world is unclear, but it will certainly be significant.

So what does constitute an external driving force? Remember: it’s an arbitrary choice where you draw the boundaries of the system. Because humankind has, to some extent, choice about what we do, it’s convenient to consider our own activities as external to the system – even though we’re very clearly part of the Earth’s ecology. It seems sensible to regard the rest of the Solar System as external, too: there are several ways in which the rest of the Solar system affects the Earth’s climate, but the Earth’s climate has very little effect on the rest of the Solar System.

Which brings us back to the question of whether the recurrent patterns in climate change are internally generated, or due to an external driving force. It seems very likely that the broad overall shape of the temperature graph, a cyclic variation of about ten degrees with a period of about 100,000 years, is driven by well understood changes in the Earth’s orbit and axial tilt (Milankovitch cycles). The main reason for this suspicion is that the frequency of the temperature changes matches the frequency of the Milankovitch cycles.

But it’s really a slightly artificial distinction between internally generated and due to an external driving force anyway. It can be (and most probably is) a bit of both: a system with feedbacks in general has one or more resonant frequencies – that is, frequencies at which it tends to oscillate (remember Butterflies, Chaos, Feedback). A recurrent driving force with a frequency close to such a resonant frequency is likely to result in a large oscillation, like a parent pushing a child on a swing in time with the swing’s natural movement. Push it out of time, and nothing much happens. So it’s a bit of both – a regular push, but also a willingness to be pushed at that frequency.

Finally, it’s interesting to think about the shape of the peaks, and particularly the different shape near the right hand end – the last few thousand years, which is relatively level. But that’s another essay I’ve still to write.

If you can get hold of Scientific American for March 2005, see How Did Humans First Alter Global Climate? by William F. Ruddiman (sadly, only the first couple of paragraphs available online for free – you have to pay for the article if you don’t have an online subscription). His suggestion is that human forest clearance and agriculture have for the last few thousand years forestalled the onset of an ice age which would otherwise be beginning by now. I've not seen this theory either confirmed or refuted, but it seems entirely plausible and explains the anomalous stability of the climate in the past 10,000 years or so.

©2011-24 Clive K Semmens